Tag

Alighiero Boetti, Arte Contemporanea, Carla Accardi, Contemporary Art, Gianfranco Baruchello, Giosetta Fioroni, Hélène Guenin, Ketty La Rocca, Lucia Marcucci, MAMAC, Maria Lai, Mario Ceroli, Mario Schifano, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Poesia Visiva, Pop Art, Tomaso Binga, Valérie Da Costa, Vincenzo Agnetti, Visual Poetry

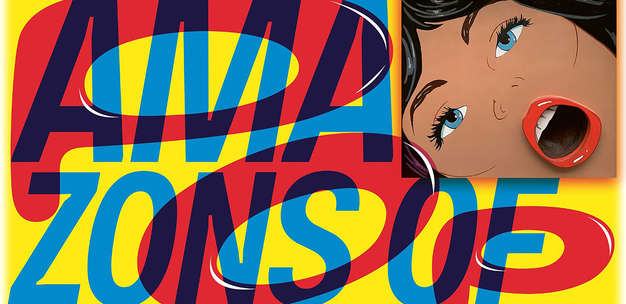

For the first time in France since 1981, the MAMAC of the city of Nice presents a major project dedicated to the Italian art scene between 1960 and 1975. Bringing together 130 works by 60 artists, “Vita Nuova” offers an unprecedented perspective on a major art scene.

“Vita Nuova. New issues for art in Italy 1960-1975” aims to uncover the extraordinary vivacity of artistic creation in Italy between 1960 and 1975, whose diversity remains very little known in France – with the exception of the works of Arte Povera artists. Between the early 1960s and mid 1970s, Italy experienced a particularly fertile and exceptional period, inextricably linked to the richness of cinema and literature of the period. Paradoxically, since the exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou National Museum of Modern Art (Paris) in 1981 – “Identité italienne. L’art en Italie depuis 1959”, curated by Germano Celant (1940-2020) – there has been no major overview of this remarkable art scene in France. Between the early 1960s and mid 1970s, Italy experienced a particularly fertile and exceptional period, inextricably linked to the richness of cinema and literature of the period. Paradoxically, since the exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou National Museum of Modern Art (Paris) in 1981 – “Identité italienne. L’art en Italie depuis 1959”, curated by Germano Celant (1940-2020) – there has been no major overview of this remarkable art scene in France. Curated by Valérie Da Costa, art historian, specialist in Italian art, “Vita Nuova. New issues for art in Italy 1960-1975” makes up for this historical gap, offering an unprecedented take on these fifteen years of creation from 1960 – which corresponds to the first exhibitions of a new generation of artists (born between the years 1920 and 1940) active in Genoa, Florence, Milan, Rome and Turin – to 1975, a year marked by the tragic death of the writer, poet and director Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975). The year 2022 marks the centenary of his birth.

This generation of artists offered up new ways of understanding and making art: they illustrated a form of vita nuova (“new life”) – a title borrowed from Dante’s eponymous book (Vita Nova) which, while serving as an ode to love, asserts a new way of writing – marking Italian art in this period and contributing to its international recognition. During the 1960s and 1970s, Italy’s transformation (industrialism, consumer society, political instability, etc.) resulted in new modes of representation. It is this historical and political context that forms the background of this exhibition. This exhibition adopts on a resolutely thematic approach and is organised around three key topics: A society of images, Reconstructing nature and The body’s memory, all considered in a porous and cross-cutting nature, in order to demonstrate the circulation of artists, forms and ideas between visual, ecological and corporeal issues. The exhibition aims to present a diverse, non-exhaustive artistic landscape, composed of a selection of artists – some of whom have been forgotten in the world of Italian art (particularly with regard to female artists) – whose work is exhibited for the first time in France and has been recently rediscovered in their own country. Developed as a multidisciplinary exhibition, “Vita Nuova” explores the links that have been established simultaneously between visual creation, design and cinema. The exhibition aims to present a diverse, non-exhaustive artistic landscape, composed of a selection of artists – some of whom have been forgotten in the world of Italian art (particularly with regard to female artists) – whose work is exhibited for the first time in France and has been recently rediscovered in their own country. The exhibition presents 60 artists, including many women artists, through a selection of 130 works and archival documents from Italian and French, public and private collections.

A SOCIETY OF IMAGES

During the 1960s and 1970s, Italy’s transformation (economic miracle, industrialism, consumer society, political instability, etc.) resulted in new modes of representation. Italian cinema was in its golden age. With the Cinecittà studios, Rome was nicknamed “Hollywood on the Tiber”. Cinema stars entered the world of the canvas, while artists used cinema in their works. The image of the woman, advertising, television, cinem a and the artistic heritage of Antiquity and the Renaissance, together with the contemporary city and questions of sexuality and gender, all became subjects to be explored. This effervescence would be counterbalanced at the end of the 1960s by increased political a nd social tensions (events in the spring of 1968, strikes in the autumn of 1969, the attack on the Piazza Fontana in December 1969, the Borghese coup d’état in 1970, etc.), eliciting a significant reaction among artists.

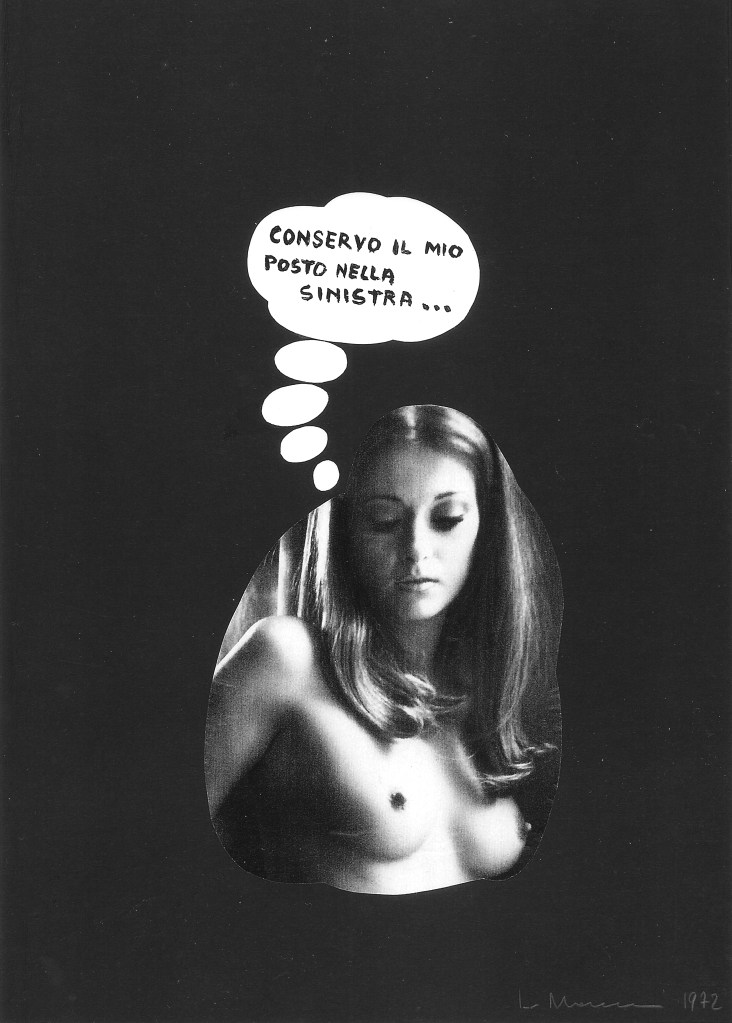

Vincenzo Agnetti, Franco Angeli, Gianfranco Baruchello & Alberto Griffi, Gianfranco Baruchello, Tomaso Binga, Alighiero Boetti, Marisa Busanel, Lisetta Carmi, Luciano Fabro, Tano Festa, Giosetta Fioroni, Rosa Foschi, Jannis Kounellis, Sergio Lombardo, Ugo Nespolo, Renato Mambor, Lucia Marcucci, Titina Maselli, Fabio Mauri, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mimmo Rotella, Mario Schifano, Cesare Tacchi.

RECONSTRUCTION NATURE

The theme of the “reconstruction of nature” (“ricostruzione della natura”) is borrowed from Pino Pascali, who affirmed its free interpretation in his works. In this highly industrialised world, the time had come to raise awareness about the excesses of our consumer society. Here, nature is represented as a resource and a central subject for certain artists who, seeking a form of degrowth, use it in their creations. As such, they develop various filmed actions that interact with natural elements (wind, sun, earth, sand and water), or even interpret it via primary and artificial materials to design sculptures and installations that recreate nature in its strictest elementarity. During these years, artists and desi gners shared a common interest in the forms of nature explored; this practice was all about bringing art into life.

Giovanni Anselmo, Archizoom, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Mario Ceroli, Piero Gilardi, Pietro Derossi con Giorgio Ceretti e Riccardo Rosso, Gino De Dominicis, Laura Grisi, Maria Lai, Mario Merz, Gina Pane, Luca Maria Patella, Claudio Parmiggiani, Pino Pascali, Giuseppe Penone, Marinella Pirelli, Ettore Spalletti.

THE BODY’S MEMORY

“That which always speaks in silence is the body” (“Ciò che sempre parla in silenzio è il corpo”), wrote is memory Alighiero Boetti. The sculpture the trace of the body just as painting is movement. In Italy in the early 1970s, many artists used their bodies as an element of reference, measurement, distortion and performance, rather than as a single material with which to interact in contrast with the spectacular and exhibitionist themes of body art. These works are born from the body or evoke its memory from a more conceptual perspective. The body is also a political object that questions gender and history through a performative approach, whether personal or collective. For some artists, this participatory experience opens itself up to the public space, thereby rendering it a form of social art.

Carla Accardi, Vincenzo Agnetti, Giovanni Anselmo, Irma Blank, Claudio Cintoli, Giorgio Griffa, Paolo Icaro, Ketty La Rocca, Eliseo Mattiacci, Franco Mazzucchelli, Fabio Mauri, Marisa Merz, Ugo Nespolo, Luigi Ontani, Giulio Paolini, Luca Maria Patella, Carol Rama, Gilberto Zorio.

Curated by Valérie Da Costa

Project Manager: Laura Pippi-Détrey

Director of MAMAC: Hélène Guenin

Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain (MAMAC) – Nice (France) 14 May 2022 – 2 October 2022

© Riproduzione riservata